Two decades later HurdleThe remaining people can still describe in detail that the Gulf coast was destroyed after the storm.

In New Orleans, many initially thought they had run the worst run, namely, until the storm overwhelmed Leves, broke the city floods. As the days passed, the situation became worse and worse.

Hurricane Katrina led around 1,400 deaths, displaced more than one million people and abandoned a loss of hundreds of billions of dollars on the Gulf coast.

While there has been diversity in recovery, some people who returned it to New Orleans have received hope in the city they love.

“a blessing in disguise”

For Torrenjet Andrews, losing everything in Hurricane Katrina opened an opportunity for a new beginning.

Andrews and his family were not able to vacate New Orleans before the category 3 storm hit.

“We are not just able to get up and can bus,” he told CBS News on August 30, 2005, after avoiding the growing water with her mother, her young children, her sister and her sister’s children. “We do not have transport. I mean, we are living Pachek-to-Pacches.”

He and his sister tied their children to their children to instigate them through the flood. Once they made it interstate, one of some places of dry land in the city, they were stranded like thousands of others.

“We stayed on the bridge and the sun started smiling,” he recalled in an interview with CBS News this week. “I remember it like it was yesterday.”

CBS News

He did not know whether anyone is coming to empty them or what their next step would be.

But after talking with the media, “Within 15 minutes, an army was pulled by the truck, removed my family from the bridge and brought us to the center of the conferences,” he said.

Andrews and his family ended in Houston, Texas, where they got an apartment, got a job and stayed for 16 years, while her children had finished school, she said.

Then he returned to New Orleans.

Andrews said, “Now, in my current life, I am not where I want to be, but I am better than that.” “It was really a blessing in disguise and it gave us a little more opportunity.”

He said that the storm made him strong and more flexible.

“If you go through the storm Katrina, you can live anything,” he said. “Some of us left only clothes on our back. Some of us did not recognize too much. Some of us did not even give bronze money in our pocket. So if you survived, all those years ago, you can survive anything.”

“Hope they know that we are still here”

After increasing the water in the entire New Orleans, the basement of the Charity Hospital started flooding. Then, because the electrical appliances were in the basement, the electricity went out.

While the flood made it difficult to take any new patient to the hospital, doctors worked to keep already alive.

Surgeon, a surgeon, Dr. Elon Maran told CBS News on September 1, 2005, “We have still found many patients on ventilator, we have found patients who need dialysis.”

This week, in an interview with CBS News, Marr recalled portable diesel-powered generators for 12 stairs flights, switched patients to ventilator operated by oxygen instead of electricity, and eating “a lot of beans” since the cafeteria and any fresh or frozen meal.

“These were bare bones, but we had enough to do what we had to do,” he said.

But with communication across the city, state officials thought that the hospital was already evacuated.

“We are listening to the radio, and we heard them the report that everyone in the charity hospital was evacuated,” said Mara. “We are looking at our patients, going, ‘No, we are not. We are not here.”

“He was a governor who was reporting this, so it was so, hopefully they know that we are still here,” he said.

It took about five days before all the patients evacuated. And when Marra called that week and recovery of one of the most difficult and challenging periods of his life, he said that he learned a lesson about leadership and your people’s care.

“I came to New Orleans to create a difference, and when it happened, I realized that more than ever, there was a need to help people step and fix us,” he said. “And I felt that if I know that I would be a hypocritical, you ran away at first sight of a bad time.”

He said that it took 10 years before the charity had a new replacement hospital. Now with a new partnership, he is expecting to help more patients for future health care systems.

“I’m glad I stayed,” he said.

“Numb to a lot of pain and pain”

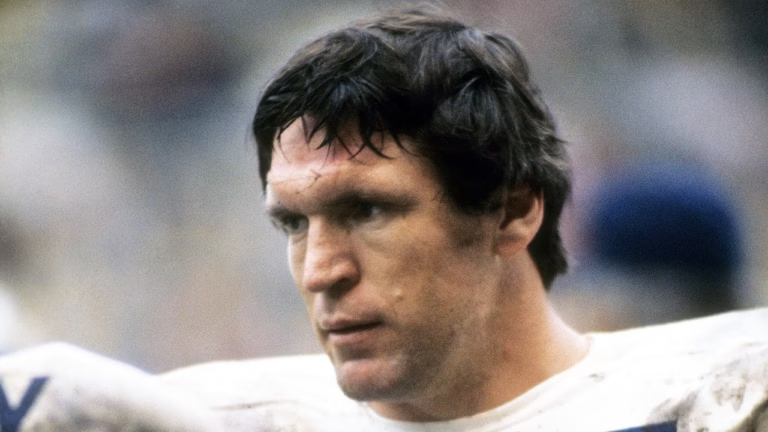

The Eddie Compass, who was the Superintendent of the New Orleans Police Department, when Katrina killed, is still physically and emotionally marks from the days after the storm.

Facing a city that was 80% under water, reduced communication, and in support of a little, Compass said that police and fire departments tried to start rescue missions and help people who took shelter in Superdome, which had gone from a safe shelter to a sadness.

Toilet facilities were overwhelmed, food and water were running less and lights came out in parts of the dome. And across the city, roads were irrelevant without boats.

“I mean, it was somewhat heavy,” he said. “In addition, I could not sleep. I did not sleep for the first three days.”

The exhaustion of the compass was clear. On September 2, 2005, in a clip aired on “CBS Evening News”, the Compass argued for its police officers.

“We have people … who have lost their families and have not been out of this fight,” he said. “I am much tired of this, but it is almost over.”

Getting out of the camera, he said, “This is the case. I don’t want to talk more.”

AFP through Getty Image

Twenty years later, the compass admitted that he broke several times amid the chaos brought by Katrina.

“Some times I broke, I broke due to my love for my heart and my city, and when I saw the people I love, and the people I know, they die, it impresses me,” he said.

The compass was not freed from personal loss – his elderly aunt and uncle died because they did not help vacate, and he said that he died of suicide of an officer in his command.

“Every day, who bothers me,” he said.

He also had a decline that caused so much damage to his hips that he needed a double hip replacement years later. The Compass pointed to the stains on its feet that are still made of all the cuts and injuries that they continued to work to help the people trapped by the storm.

“People have no idea of personal pain during Katrina,” he said. “I was numb to a lot of pain and pain because I had to help those who were alive.”

He recalled a moment when he was helping people go into a bus to vacate people, and a person wheel a dilapidated person in a wheelchair, wondering what to do next. He thought that the person needed medical help in the wheelchair, but quickly realized that he was already dead.

“I took a blanket and I put it on it and just rolled it in the corner,” he said. “I could not mourn him. I couldn’t worry about him, because there are many other people who needed my help and attention, and it was very disappointing for me in those moments, but I had to block it.”

During the first five days after the storm, media focus focused on crime and loot in the city. However, there was a lot of looting because people had no other means of access to food and water. He had no home and many people were not identified.

“People were hungry,” said Compass. “People needed help.”

There were some people Shot by police Or CautiouslyCompass said that he never ordered to shoot alleged looting.

“I never called for martial law. I couldn’t do it,” he said.

After Katrina, the compass said that she was expelled from the police department more than political disagreement.

“It was trying very emotionally because I had done my work and my word was not taken,” the Compass said. But, he says, “God shifted me in the other direction.”

Compass worked for the state school system for 10 years and developed programs to help less children in Louisiana. He now works as an individual trainer and freelance bodyguard. Close to the age of retirement, he is eager to spend more time with the family.

Asked what lessons should be shared with other cities for the future, he said that he feels that most of the cities are now more ready than New Orleans.

“We were guinea pigs. We were prototypes, you know, how to handle it when it happens, but it is a situation that we made a lot of mistakes, but we did a lot of good things,” he said. “We saved a lot of life as a police department and a fire department, and many people really lost the fact that we started those boat missions before helping anywhere.”